Operating a tow truck is a critical job that often requires navigating complex regulations. For local drivers, auto repair shop owners, and property managers alike, knowing whether a Commercial Driver’s License (CDL) is necessary can be challenging. This article dives into the requirements for driving tow trucks, highlighting the need for a CDL, especially for larger vehicles. In understanding the nuances of Class B CDLs and special endorsements, readers will gain clarity on regional variations and overall implications. Through this exploration, we aim to empower our audience to ensure compliance and safety on the road.

null

null

Weight, Responsibility, and Rule: How a Class B CDL Shapes Tow Truck Operation

Tow trucks occupy a unique niche in the world of roadway assistance. They arrive at scenes that mix urgency with risk, where vehicles can be physically large, highways are busy, and conditions are rarely ideal. In that environment, the operator’s license does more than certify a skill set; it signals a baseline of training, safety discipline, and regulatory compliance. The central question—do you need a CDL to drive a tow truck?—has a straightforward answer in most contexts, but the nuance behind that answer matters a great deal for anyone choosing a path in the towing and recovery industry. When the weight and configuration of the vehicle come into play, the rules become a practical guide to what you can and should do on the road, and they also illuminate why the license is a cornerstone of professionalism in the field. A Class B Commercial Driver’s License (CDL) is the standard credential for many tow operators, especially those driving the common heavy wreckers and flatbeds that recover vehicles from the side of a highway or from a wreck site. The threshold is not arbitrary: the federal framework defines a commercial motor vehicle by weight and function, and that framework is designed to ensure operators have the training to handle a vehicle that can cause significant harm if mishandled. In this sense, the CDL is less about prestige and more about a measured commitment to safety and public accountability.

The heart of the matter lies in GVWR, or gross vehicle weight rating. If the tow truck itself weighs more than 26,000 pounds GVWR, federal rules kick in that typically require a CDL. But the plot thickens when the tow truck is used to haul a separate vehicle that weighs more than 10,000 pounds. In that scenario, even a lighter carrier can become a CDL-required operation due to the potential hazards associated with moving a heavy, unstable load on public roads. This dual pathway—vehicle weight or towed weight—helps explain why the Class B license has become the de facto standard for most tow operators. The Class B CDL is designed to permit a driver to operate a single vehicle with a GVWR exceeding 26,000 pounds, a common profile for wreckers, flatbeds, and many specialized recovery units. The practical implication is clear: if your primary tool is a heavy, non-articulated vehicle, you likely need a Class B to perform standard towing duties legally and safely.

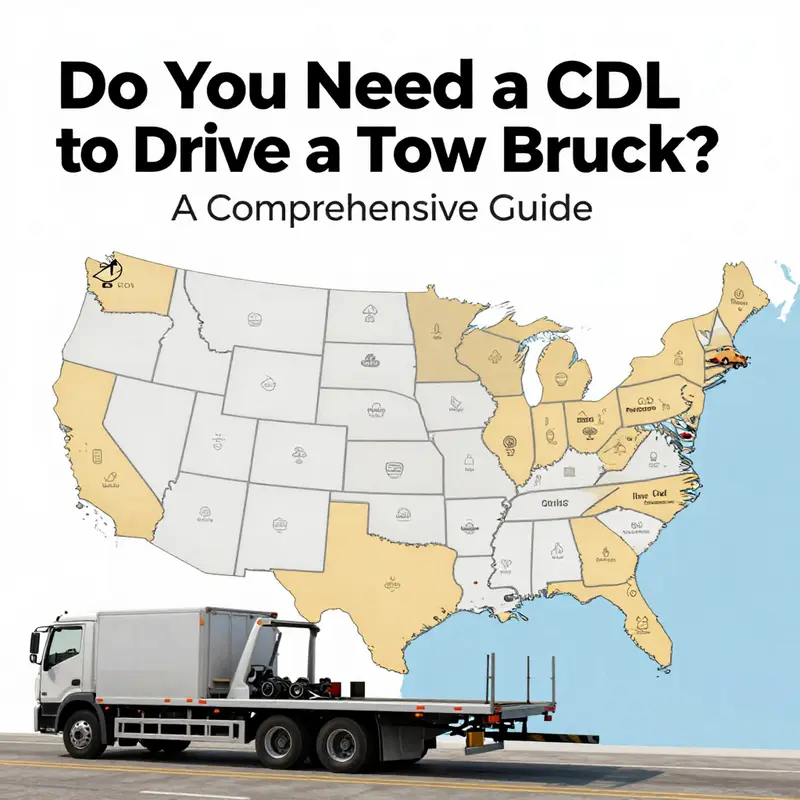

Yet licensing is not a one-size-fits-all checklist. The federal baseline provides a framework, but states retain authority to adapt and refine certain rules. Some states have additional requirements or lower thresholds that trigger CDL needs for particular configurations or use cases. Because regulations are a mix of federal guidance and state adaptations, savvy operators treat the licensing path as something to verify with the local DMV in their jurisdiction. The importance of this step cannot be overstated. A tow operator who assumes a license covers all situations without checking state specifics may run into disruptions in operation, from suspended work to insurance concerns. In short, diligence in understanding local requirements protects both the operator and the business and helps prevent scenarios where a tow unit grounded on the side of a highway becomes a safety incident in waiting.

Even within the Class B framework, endorsements matter. The T endorsement, which stands for Trailer, is typically required if the tow truck pulls a trailer. The P endorsement, or Passenger, may be necessary if the vehicle is used to transport people, a scenario relevant for some recovery operations that include a crew or transport of technicians. The S endorsement for school buses is not commonly needed for tow operations. These endorsements are not mere add-ons; they reflect a more granular understanding of what the vehicle is carrying and how it is used, and they capably signal that the driver has been tested on the additional complexities of responsibilities beyond merely steering a heavy machine.

Beyond the license itself, the practical path of training, testing, and ongoing compliance is a continuous process. The CDL process typically starts with a state-administered program that includes a knowledge examination covering vehicle inspection procedures, basic safe driving practices, and regulations particular to commercial operations. The knowledge test is followed by a DOT physical exam, intended to confirm the driver’s fitness for the demands of operating a large vehicle. A clean driving record is highly valued, not only for the licensing process but for employment prospects and insurance considerations. The training that accompanies CDL attainment is more than rote memorization; it is an apprenticeship in the careful handling of heavy equipment, the management of space around a large vehicle, and the discipline to perform thorough inspections in the face of time pressure. These skills translate directly into safer tow operations, especially at accident scenes or in heavy traffic where precision can prevent a secondary incident.

For many in the towing and recovery sector, a Class B CDL is a gatekeeping credential. Employers routinely require it as a baseline qualification. A driver without a CDL, even if mechanically adept, often runs into structural barriers to employment in this field. The license serves as a signal of readiness to handle the responsibilities of towing, recovery, and roadside service at scale. It also unlocks opportunities for advancement, including roles that involve more complex equipment, larger fleets, or supervisory responsibilities. In this sense, the Class B CDL is not simply a license to drive; it is a professional standard that aligns the individual with a broader industry expectation of safety, accountability, and service reliability.

The journey to Class B certification is carefully structured. Prospective drivers must meet both federal and state requirements, which commonly include passing a DOT physical exam, maintaining a clean driving record, and completing a state-approved training program. The process is designed to filter for individuals who can manage the weight and momentum of heavy vehicles under diverse conditions. A typical path begins with a vocational or community program focused on heavy vehicle operation, followed by the standardized tests that assess a candidate’s understanding of vehicle inspection, basic control of a heavy vehicle, and the specific regulations governing commercial driving. The requirements emphasize not only performance behind the wheel but also the discipline required to perform routine inspections that protect the driver, the vehicle, and the public.

The weight of the rulebook has practical effects on how a tow operation is conducted every day. A truck that qualifies as a CMV—because it weighs over the 26,000-pound threshold or because it is used to tow a very heavy vehicle—demands compliance with hours-of-service rules, vehicle inspections, maintenance logs, and other regulatory duties designed to minimize fatigue and errors on the road. The result is a culture of safety that percolates through the organization, from the driver to the dispatcher to the shop technician who keeps the fleet road-ready. This culture matters because towing is rarely a solitary act. It is a coordinated effort involving communications, route planning, and situational awareness at the scene of incidents that can evolve rapidly. The license anchors this culture by ensuring that those who operate the vehicle have demonstrated a baseline mastery of the essential skills and the regulatory context in which those skills are applied.

From a career perspective, the Class B CDL opens doors that are not always accessible to non-credentialed drivers. It becomes a professional standard that signals a level of training, responsibility, and commitment to safety that resonates with employers and clients alike. The workflow of a tow operation often involves responding to unpredictable events, making quick judgments about weight distribution, tire traction, and the safe extraction of disabled vehicles from precarious positions. A driver equipped with a Class B license approaches these situations with a framework that emphasizes vehicle performance, control, and the procedural steps required to bring a scene to a safe conclusion.

As the industry continues to evolve, the integration of standardized practices—such as those that emphasize heavy-duty rescue operations and fleet readiness—helps align operators with broader safety goals. This alignment is not merely about regulatory compliance; it is about delivering reliable, professional service in circumstances that demand precision and calm under pressure. The narrative of licensing, weight, and responsible operation thus becomes a story not only about what is legal but about how to contribute to safer roads and more effective recovery operations. For readers who want to explore how standardization can support decision-making in high-stakes environments, the broader discussion of heavy-duty rescue operations offers a useful lens into how teams coordinate, communicate, and execute under pressure. standardization in heavy-duty rescue operations

In pursuing this licensing path, aspiring tow professionals should keep in mind that the journey is not a one-time milestone but a process of ongoing compliance and skill development. Maintaining a Class B license involves periodic renewals, ongoing medical certification, and staying current with state rules that affect the daily realities of towing work. It is a commitment to continuous improvement that aligns the driver with a profession defined by service, safety, and accountability. For those who are building a career in this field, the CDL is less about a certification of completion and more about a framework for excellence—an explicit acknowledgment that operating heavy equipment on public roads demands a high standard of preparation and responsibility. In the end, the question of whether you need a CDL to drive a tow truck is answered by the anatomy of the job itself: weight, configuration, and the weight of the obligation to keep people safe on cramped, crowded, and sometimes dangerous roadways. For a deeper dive into the specifics of Class B CDL requirements and how they apply to different vehicle types, refer to trusted state resources that outline the precise thresholds and prerequisites, and remember to consult the official state DMV guidance for your area. External resource: https://www.dmv.org/vehicle-licenses/class-b-cdl.php

Endorsements and the CDL Maze for Tow Truck Operators: Navigating State Rules and Real-World Requirements

When people ask whether you need a CDL to drive a tow truck, the short answer is both yes and no—depending on the vehicle’s weight, configuration, and where you operate. Tow trucks cover a wide range of equipment, from light-duty wreckers to heavy rotators, and the rules shift with the numbers on the scale. At the core, federal guidance classifies many tow trucks as commercial motor vehicles (CMVs) once they pass certain weight thresholds or are involved in towing operations that push into heavier territory. The practical effect is this: if your tow truck itself weighs more than 26,000 pounds gross vehicle weight rating (GVWR), or if you’re using a tow truck to haul another vehicle that weighs more than 10,000 pounds, you’re generally looking at a CDL requirement. That baseline comes from the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) and its regulations around CMVs, but the story doesn’t stop there. The exact licensing you need hinges on the state you operate in, because state DMVs adapt the federal framework to local road, worker, and safety realities.

Most tow trucks that stay within the ordinary range—what many fleets run day to day—fit neatly into Class B CDL territory. A Class B license is designed for operating a single vehicle with a GVWR above 26,000 pounds, a category that encompasses the majority of standard tow trucks. Yet even with a Class B, the job can be more complicated than simply turning the ignition. The endorsements you carry can shape what you can operate and how you can operate it. The T endorsement, short for Trailer, is the one most people associate with towing. If your tow truck pulls a trailer, you’ll likely need the T endorsement. The P endorsement—standing for Passenger—comes into play when the vehicle is used to transport people, such as a wrecker that may also ferry technicians or clients. The S endorsement, which addresses school buses, usually sits outside the tow truck domain, but the landscape can blur when a vehicle has multiple functions.

Beyond endorsements, the weight thresholds and the specifics of the vehicle’s configuration matter. Some tow trucks are configured in a way that makes them CMVs even if their GVWR is technically below the 26,000-pound line, due to their towing arrangement or because they’re engaged in certain commercial activities. States can push the threshold in different directions, creating a patchwork of requirements that can surprise operators who cross borders for work or who relocate fleets. For this reason, operators should treat the DMV as the compass. Your state’s DMV will confirm the exact combination of weight, vehicle class, and endorsements you must hold to legally and safely perform tow work in your jurisdiction.

The New York example offers a pointed case study in how endorsements can diverge from one state to another. In New York, a specialized endorsement—often referred to by the letter W—applies specifically to tow truck operation. This W endorsement has been part of the state’s licensing framework since January 22, 1995, and it applies regardless of the particular type of tow vehicle you operate. The W endorsement is not a universal requirement nationwide; it is a state-specific credential designed to address the unique duties and safety considerations that towing work in New York presents. For anyone operating or planning to operate a tow truck in New York, that W is a constant presence in the licensing checklist. The precise eligibility criteria, testing requirements, and application procedures for the W can change, so the state DMV’s official pages are the authoritative source. Those resources outline the steps to obtain the W, the testing sequence, and the medical and background clearances that may accompany the process.

This state-specific nuance underscores a broader point: the CDL framework provides the skeleton, but the endorsements flesh out the functional requirements. A fleet that runs in multiple states confronts another layer of complexity. If a driver moves from a state where a W endorsement exists to a state that doesn’t use the same designation, the driver may need to adapt to that jurisdiction’s own endorsement structure or licensing rules. Conversely, a driver moving from a state with fewer tow-specific endorsements might encounter added requirements in a state with a more robust towing-by-CMV framework. The practical takeaway is simple: when planning hiring, training, and compliance for tow truck operations, consult both the federal baseline and the state-specific rules. The DMV’s official guidance will spell out precisely which license class, which endorsements, and which medical certifications are required for your particular operation.

Beyond the mechanics—CDL class, endorsements, testing, medical requirements—there is a culture of compliance that threads through successful tow operations. The path to licensing is not a one-and-done event; it’s a continual process of staying current with regulations, maintaining the driver’s record, and aligning operator capabilities with the demands of the work. Tow operators frequently juggle service delivery, roadside safety, and regulatory compliance all in one shift. Training programs, employer policies, and state regulations converge to shape a driver’s ability to perform day after day without risking penalties or jeopardizing safety on the road.

To bring this to life, consider the workflow that a typical tow operator might navigate on a regular basis. A technician who operates a mid-range wrecker with a GVWR just above 26,000 pounds may need to secure a Class B CDL with a T endorsement, ensuring the ability to tow trailers as needed. If that same vehicle routinely carries passengers in addition to equipment, the driver may require the P endorsement as well. If the job places the vehicle into a specialized category that touches on school transportation regulations or requires specialized routing or operation, additional endorsements could come into play. The licensing landscape is not simply about knowledge of driving; it’s about a disciplined approach to risk management, vehicle inspection, and the ability to operate in potentially hazardous roadside environments.

The practical question of “do you need a CDL to drive a tow truck” therefore becomes a triad: determine the GVWR and towing configuration, verify the state’s endorsement requirements, and align training and testing with that combined assessment. A safe, compliant tow operation is built not just on the right license, but on a system of checks and ongoing education. Operators should be prepared to show documentation of the vehicle’s GVWR, the specific endorsement mix carried, and the medical certification that accompanies the CDL. Fleets benefit from maintaining updated driver qualification files, conducting periodic refresher training, and establishing clear internal procedures for verifying that every driver’s license and endorsements match the vehicles they operate.

For readers seeking practical, jurisdiction-specific guidance, a resource anchored in the broader conversation about towing licenses is available in the industry literature. You can explore further insights and perspectives on towing operations in the Santa Maria Tow Truck Blog, which offers practical commentary on fleet standards and readiness for emergency response scenarios: Santa Maria Tow Truck Blog.

This chapter, while focusing on endorsements and the CDL framework, is designed to fit into a larger narrative about the licensing landscape for tow truck operators. It reflects the fluid reality that licensing is not a single milestone but a continuum of compliance, training, and prudent preparation. By understanding the weight thresholds, the role of endorsements such as T and P, and the state-specific nuances like New York’s W endorsement, drivers and fleets can approach licensing with confidence and clarity. The bottom line is that the CDL is a critical gate, but the endorsements and state adaptations are the switches and levers that allow a tow truck to move legally and safely through the road network.

For a broader federal view on how CMVs are regulated and what qualifies as a CMV under FMCSA rules, reference the official FMCSA resource. This external guidance helps frame the licensing decisions within the federal safety framework: https://www.fmcsa.dot.gov

The Patchwork of CDL Rules: How State Variations Shape Tow Truck Licensing

The question, do you need a CDL to drive a tow truck, does not have a single answer that fits every mile of the United States. Instead, it maps onto a landscape of state rules that extend and interpret federal guidelines in different ways. For someone managing a tow operation or choosing a licensing path for a new operator, this patchwork matters as much as the weight on the vehicle’s plate. The federal baseline, established by the FMCSA, sets the core rules for commercial motor vehicles, but the way those rules apply to a tow truck depends on weight, configuration, and how the truck is used. In practice, this means that two fleets in neighboring states can face different licensing requirements for essentially similar equipment. The practical upshot is simple: compliance starts with knowing both the federal yardstick and your state’s idiosyncrasies, then staying current as rules shift with changing fleets and technologies.

At the heart of the federal framework is the concept of the Commercial Driver’s License as a threshold to operate a commercial motor vehicle. The FMCSA defines CMVs by weight and structure, and a tow truck usually falls under this category when it crosses certain thresholds. The most widely cited benchmark is the gross vehicle weight rating (GVWR) at 26,001 pounds. If the tow truck itself weighs more than 26,000 pounds GVWR, it is treated as a CMV. Likewise, if the operator uses the tow truck to tow another vehicle that, when loaded, exceeds 10,000 pounds, that scenario can trigger CDL requirements as well. This formulation is why Class B is often the standard credential in tow operations: a Class B CDL covers a single vehicle with a GVWR above 26,000 pounds, which includes most conventional wreckers and rollback tow trucks. Yet even within Class B, the endorsements and the precise state interpretation of the rules can vary, nudging a fleet toward or away from extra training and licensing.

Endorsements are the next layer of state-specific detail. The T endorsement, for example, is the minimum many operators expect to pull a trailer. But there are other endorsements that may come into play depending on the vehicle’s equipment and duties. The N endorsement covers tank vehicles, while the H endorsement governs hazardous materials. A wrecker that occasionally transports passengers might also trigger a passenger endorsement in some jurisdictions. And some states still show close attention to other special considerations, like whether the tow truck is configured to transport school children or specialized rescue teams. Even when the core CDL is in hand, endorsements flow from what the vehicle carries, how it carries it, and where the vehicle operates. The result is a layered licensing picture rather than a single all-purpose permit.

State-by-state variations begin with how a jurisdiction defines a CMV and when a tow truck crosses from the realm of standard autos into the commercial lane. Some states classify a tow truck with a GVWR of 26,001 pounds or more as a commercial vehicle requiring a CDL, regardless of whether it is used to tow something else or simply to move itself. Other states may hinge CDL necessity on the purpose of the vehicle, such as whether it is used to transport hazardous materials, to move more than a certain number of passengers, or to carry a load that, once on the road, pushes the vehicle over weight thresholds when loaded. The implication is not merely about a license. It is about training standards, medical requirements, and testing regimes that shape a driver’s readiness for the road.

The most visible effects of this state-level tailoring appear in the endorsements and their practical demands. Some states require a T endorsement for any tow operation that involves pulling trailers, even if the trailer is not carrying hazardous materials. Others implement stricter rules for certain configurations, where the towed vehicle’s weight, the presence of a flatbed, or the use of a wheel-lift mechanism changes the licensing calculus. There are jurisdictions that require an N endorsement if the tow operation involves tank vehicles or integrated liquid transport, while others keep such discussions out of the towing conversation entirely. A few states still align more closely with traditional definitions and defer to the federal standard, but even those that drift closer to federal minimums often demand additional testing or medical clearance beyond what FMCSA requires for the general CDL.

For fleet managers and operators, these differences translate into concrete planning decisions. Licensing costs rise when a state requires multiple endorsements for a single fleet, and training calendars shift to accommodate state-approved curricula that cover the exact vehicle configurations and end-use scenarios in play. A trailer-tow operation may need to prepare drivers for more stringent tandem-axle or combination vehicle testing, while a pure tow of a single vehicle might stay within a simpler framework in one state but require more complex endorsements in another. The diverging rules can also influence which vehicles are deployed in particular regions. Some fleets choose lighter configurations or different tow mechanisms to stay within a more consistent licensing path, reducing administrative overhead and minimizing the risk of non-compliance when a truck crosses state lines.

The compliance picture is not static. States periodically update their manuals, adjust weight thresholds, and reexamine endorsements as the fleet mix evolves and as safety data from the field accumulates. That fluidity makes proactive compliance essential. Tow operators should begin by confirming their state’s DMV guidelines and then verify how those guidelines interpret the federal framework. This often means a structured review of the state licensing manual, a talk with a licensing specialist at the DMV, and a realistic assessment of each truck’s GVWR and its actual use. Documentation matters as well: keeping a record of vehicle specifications, the payload actually carried, and the precise nature of towing operations helps to avoid disputes when licensing questions arise. In many jurisdictions, even if the vehicle technically qualifies as a CMV on paper, the practical operations—such as when the tow truck is on a city street at night or responding to an incident on a highway—may trigger additional risk-management considerations that the state wants to see reflected in the operator’s credentials.

The complexity of state variations makes it helpful to consider real-world scenarios. A heavy tow truck with a GVWR just over the 26,000-pound line might be treated as a CMV in one state, obligating a CDL, while in a neighboring state the same vehicle could be viewed through a narrower lens if it is used only to tow lighter vehicles or if the vehicle’s own weight is the sole factor considered. Serving as a reminder that these rules are not purely abstract, the practical import is clear: stay aligned with the local DMV, keep up with endorsements that match the variety of tow operations performed, and plan for potential licensing adjustments when cross-border work becomes a factor. The operator who embraces this approach reduces the risk of penalties, service delays, or vehicles being pulled off the road for inspection while en route to a scene.

As you navigate this terrain, a useful step is to engage with public-facing resources that summarize state practice, while recognizing that the official text governs. For example, certain state advisories address weather-related duties and how they intersect with licensing considerations. This is especially relevant for operators who must adapt to rapidly changing conditions, such as icy highways or storm-affected roadways, where having the right licensing and endorsements in place becomes part of a broader safety and readiness plan. You can explore state-specific guidance and real-world implications in related discussions about winter planning and regulatory adjustments for tow operators, including detailed considerations on how weather events influence policy and training, here: winter storm regulations for tow operators.

Ultimately, the central thread across the state landscape is a simple one: if your tow truck is heavy or if it is used to tow a heavy vehicle, a CDL is almost certainly required. But the precise class, endorsements, and even the urgency of obtaining them depend on where you operate and how your fleet is configured. The best practice is to start with a clear inventory of each vehicle’s GVWR, identify the actual towing tasks performed, and then consult the state DMV for the exact licensing matrix that applies to your fleet. In parallel, maintain ongoing dialogue with your drivers about the rules that govern their licenses, because changes in the fleet’s operating pattern or in state policy can shift licensing needs quickly. This is not merely a bureaucratic exercise; it is a core facet of road safety, professional accountability, and dependable service delivery.

For a broader federal frame of reference, you can consult the FMCSA’s regulatory overview, which outlines the core standards that shape state practices and highlights where state adjustments most often occur. This is a valuable complement to the state-by-state guidance and helps ensure that an operator’s licensing strategy remains aligned with nationwide safety expectations. For the latest federal regulations, visit: https://www.fmcsa.dot.gov/regulations/.

null

null

Final thoughts

Understanding whether you need a Commercial Driver’s License (CDL) to drive a tow truck is crucial for compliance, safety, and smooth operations. As outlined, the requirements depend on vehicle weight, configuration, and state regulations. Having a Class B CDL and any necessary endorsements not only keeps you in line with the law but also enhances your skills and professionalism. In an industry that prioritizes safety and responsibility, ensuring you meet all regulatory standards is essential for your success.