Understanding whether you need a Commercial Driver’s License (CDL) for operating a flatbed tow truck is crucial for local drivers, auto repair shops, dealerships, property managers, and HOA administrators. The requirements vary based on vehicle weight, state regulations, and specific operational circumstances. This guide will clarify the CDL requirements, helping you make informed decisions. Each chapter will delve into essential aspects, from weight limits and state-specific regulations to the implications of vehicle combinations and special licenses for hazardous materials, ultimately equipping you with the knowledge to comply with regulations while ensuring safety and efficiency.

Weight, Warrants, and the CDL Threshold: Navigating Flatbed Tow Truck Licensing

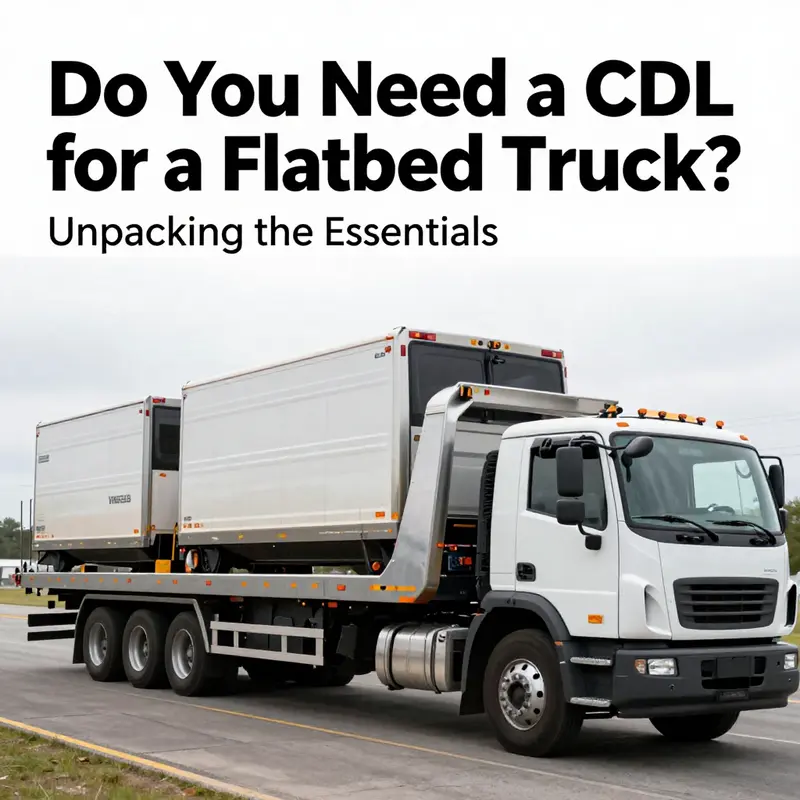

On the street, a flatbed tow truck is a lifeline between breakdowns and mobility. Yet behind every dramatic recovery lies a thread of law that defines who can drive, what they can tow, and under what conditions. The CDL question for flatbed operations isn’t a simple yes or no; it hinges on weight, configuration, and the way the work is performed. Federal rules set a 26,001-pound line on which CDL designations pivot. If the gross vehicle weight rating, GVWR, of the tow truck or the combination exceeds this threshold, a CDL is required. It’s the combined weight that matters most, not just the truck alone. A flatbed with a powerful engine and a heavier bed may push over the line even when the truck itself seems ordinary. The class you need depends on how the vehicle is built and how it’s used. A single-unit flatbed over 26,001 pounds typically requires a Class B CDL. If the equipment is part of a combination vehicle, such as a tractor-trailer setup, a Class A CDL may be required, even if the equipment weighs less than 26,001 pounds. The logic here is simple: the vehicle’s total legal weight and the number of vehicles connected to it determine the license class. An important nuance is the weight of the towed vehicle. If the truck pulls a heavy car, bus, or another heavy vehicle, the combined weight can push the GCWR over the threshold and trigger a higher CDL class. This means a tow operator with a mid-size flatbed could still need a Class A or B CDL depending on the payload and how the vehicle is arranged. It’s not just the flatbed’s rating; it’s the entire hauling configuration that matters. There are exceptions and complications. Transporting hazardous materials requires the appropriate endorsement on your CDL. Interstate commerce introduces additional requirements and testing. Some operations inside a single state may be covered by state licenses rather than federal CDL standards, but many states align with the 26,001-pound threshold. In practice, most heavy-duty flatbeds used in professional towing are configured to exceed the GVWR, making a CDL a standard part of the job. The safer approach is to verify the rating and to understand the specific rules that apply to your work location. How do you determine your exact requirement? Start with the GVWR plate on the tow truck itself. Then consider the towed vehicle and the combined weight you expect to haul. If the vehicle is a single unit over 26,001 pounds, plan for a Class B license. If the vehicle forms a combination and the combined weight meets or exceeds 26,001 pounds with a towed vehicle over 10,000 pounds, you’ll need a Class A. The line gets blurred when the payload changes from day to day; administrative rules rely on the documented GVWR and GCWR values, not hypothetical capabilities. In short, the truck’s label and the intended use determine the license. For operators, this information isn’t merely regulatory trivia. It affects training pipelines, insurance requirements, and the day-to-day risk management on calls. A CDL-trained operator is not only allowed to drive; they are also subject to ongoing medical exams, federal recordkeeping, and compliance with hours-of-service rules. This means that choosing a flatbed that sits comfortably within a legal weight category can simplify scheduling, reduce the need for additional endorsements, and lower administrative overhead when a fleet responds to emergencies or routine recoveries. In the field, knowing you’re within the right class reduces on-scene friction with law enforcement and helps you maintain a safer, more reliable operation. Industry practice often converges on a practical rule: if your equipment and typical loads push you near the 26,001-pound line, invest in the appropriate CDL. Even if you occasionally service smaller jobs, having the correct license reduces the risk of fines, license suspension, or unexpected delays that can escalate an emergency response. Fleet managers increasingly emphasize licensing clarity, not only to stay compliant but to standardize training, equipment, and response protocols. The result is a more predictable operation and a more trusted presence on the road. When regulations change or when a operator moves into a different market, it pays to consult authoritative sources. A quick look at the regulatory landscape through the state and federal portals clarifies which loads count toward the GVWR and GCWR. In regions prone to winter weather that creates additional hazards on the roadside, operators may find that extra precautions and updated procedures are required. For those navigating such conditions, see Winter Storm Regulations for Tow Operators. This resource helps crews plan for the unexpected and align licensing with practical field needs. Winter Storm Regulations for Tow Operators Ultimately, the question ‘Do you need a CDL for a flatbed tow truck?’ does not have a universal answer for every vehicle. It depends on the number and weight of the vehicles hauled, the truck’s GVWR, and how the work is structured. The simplest path is to treat licensing as a design parameter in the fleet, not a bolt-on after you purchase equipment. Ask for the GVWR and GCWR from the seller or manufacturer, pull the official plate from the chassis, and verify this with the DMV or FMCSA. For official guidance, refer to the FMCSA regulations at https://www.fmcsa.dot.gov.

CDL Requirements for Flatbed Tow Trucks: Weighing Weight, GVWR, and GCWR

Determining whether a CDL is required to operate a flatbed tow truck depends on weight and the regulatory framework. In the United States, a CDL is typically required when the vehicle you drive has a GVWR of 26,001 pounds or more, or when the combined weight of the truck and the towed vehicle exceeds thresholds that trigger higher driver qualifications. This approach centers on ensuring operators have the training and safety discipline needed to manage heavier equipment, longer stopping distances, and complex load securement. However, there are nuances: GVWR is the truck’s own maximum weight, while GCWR represents the maximum combined weight of the tow vehicle and the towed load. When the towed vehicle’s weight is included, some flatbed operations push into CDL territory even if the truck alone would not. Weight alone is not the whole story; the combination of vehicle and load determines licensing needs.

State and local rules add complexity. Some states align with the federal threshold but apply stricter exemptions for certain towing tasks or private operations. Always check the state DMV or equivalent licensing authority; the FMCSA governs interstate commerce but states tailor endorsements and classifications.

Practical implications include training prerequisites, medical requirements, and load securement. A CDL is a package of competencies, including inspection, brake systems, coupling and uncoupling, and safe operation of heavy vehicles. For flatbeds, understanding weight distribution and load securement is essential.

To plan responsibly, document the GVWR of each flatbed unit and typical weights of towed vehicles. Build a GCWR-based worksheet to flag combinations over 26,001 pounds and discuss licensing steps with the state DMV if needed. When expansion includes interstate customers, ensure endorsements align with the work.

A final note: always consult official sources—your state’s DMV resources and the FMCSA guidance pages—for the most current rules, thresholds, and endorsements.

The Weight Equation: Do You Need a CDL for Flatbed Tow Trucks When Vehicle Combinations Push the Limits

A flatbed tow truck sits at the edge of a job, its bed ready to cradle a heavy vehicle onto steel, straps, and hydraulics tightening like a quiet, patient promise. In those moments, the decision about whether you need a Commercial Driver’s License (CDL) comes down to a single but stubborn fact: weight. Not the weight you see on a banner or a sticker, but the practical weight that shows up in the math of the road. The rule of thumb has long been simple in the public eye—CDLs are for big trucks. Yet for flatbed operations, the line blurs once you factor in the entire load the vehicle is expected to carry, including what the tow truck itself is hauling or towing, and whether the operation travels across state lines or handles hazardous materials. The core idea, echoed by safety regulators and industry veterans alike, is that the authority to operate hinges on weight, not a single machine’s capability in isolation but the combined presence of the truck and its payload. When the numbers shift past a certain threshold, licensing becomes a baseline obligation rather than a professional afterthought.

In the United States, the commonly cited threshold begins with gross vehicle weight rating (GVWR). If a vehicle has a GVWR of 26,001 pounds or more, the operator is generally required to hold a CDL. This applied weight standard, while straightforward in concept, grows more nuanced when a flatbed tow truck is used to haul another vehicle or when a trailer accompanies the operation. The key factor is the total weight of the vehicle being operated, not just the tow truck’s standalone mass. A flatbed that hauls a car or truck can push the combined weight beyond the 26,001-pound line even if the truck itself sits below it. In practice, many flatbeds are designed to move some of the heaviest loads on the highway, which means the combination’s weight often becomes the deciding element for CDL eligibility. The math is simple but unforgiving: add up the numbers from the tow truck, the towed vehicle, and any trailer that accompanies the operation, and if the total exceeds 26,001 pounds, a CDL is typically in play. This framework ensures a trained, regulated driver is at the wheel when the sheer mass of a vehicle is in motion on public roadways.

The conversation does not end there. If the operation involves a trailer, the combined weight must be accounted for as a whole. Even if the flatbed’s GVWR is modest, the act of pulling a heavy trailer—or the vehicle on the bed—can tip the scales into CDL territory. That is why many operators describe the situation not as a single vehicle assessment but as a weight management problem: what will the truck and its load weigh on the highway under typical operating conditions? Everything from fuel, passengers, and equipment to the approximate weight of a mounted windshield or additional gear can push the total into a higher category. The practical effect is clear: a decision that seems straightforward at the shop door may require a CDL once the truck leaves the driveway and becomes part of a highway-weight equation.

Beyond the basic weight threshold, there are situations that carry CDL implications even when the weight looks compliant on the face of it. If the operation crosses state lines in interstate commerce, many states require CDL coverage regardless of the exact weight of the vehicle, because the risk increases with scale and distance. The handling of hazardous materials further complicates the licensing landscape. If a tow operation involves Hazmat, even with a lower weight, endorsements may be necessary. Related endorsements, such as Doubles/Triples for multiple trailers, can also come into play when a flatbed is part of a larger trailer arrangement. The takeaway is practical and persistent: licensing decisions must reflect not only the weight but also the intended use and the nature of the cargo. When weight alone does not capture all risk factors, endorsements serve as the regulatory bridge that closes those gaps.

This is where the field intersects with standards, training, and safety culture. Industry guidance that reflects real-world operations emphasizes not only compliance but the broader aim of reducing risk on busy roads. In daily practice, drivers and fleet managers often rely on a combination of weight checks and regulatory checks. They review the GVWR plate on the vehicle, estimate the loaded weight of any towed unit, and consider whether a trailer is attached. They factor in anticipated fuel loads, ballast in the vehicle being towed, and any equipment mounted on the flatbed. If the sum threatens to breach the CDL threshold, they pivot to a CDL plan, arrange the necessary endorsements, and adjust scheduling to ensure compliance before the job begins. The discipline of doing the math before the wheels turn pays dividends in safety, insurance costs, and overall reliability on the road.

To keep the discussion grounded in practice, consider how this approach translates into day-to-day decision making. A shop or operator evaluating a flatbed job will first locate the GVWR on the plate of the tow truck. If the vehicle’s own rating sits at or above 26,001 pounds, the operator has the CDL question answered in the affirmative for the base operation. If not, they still need to account for the weight of the payload. They estimate the weight of the vehicle on the bed or the weight being hauled by the tow truck and add any trailer weight if a trailer is involved. If the resulting total lands above 26,001 pounds, a CDL becomes a necessary credential for the driver. If the weight is clearly under the threshold, the operation may proceed without a CDL, but careful attention to the details remains essential—especially if the job shifts toward interstate routes or the cargo category changes. The decision tree is not a single fork in the road but a series of checks that must be completed with diligence to ensure regulatory compliance across every job.

Those checks are rarely solitary. Endorsements can shape a fleet’s capability more than a change in vehicle equipment alone. Hazmat endorsements, for example, are not optional for certain cargoes; they are a legal requirement that ensures a driver has trained to handle dangerous materials safely. Doubles/Triples endorsements become relevant when a flatbed setup works in concert with additional trailers, a reality for some emergency and heavy-rescue operations where multiple platforms are used to secure a payload. For operators, the practical implication is straightforward: a flatbed truck’s licensing needs are dynamic, influenced by both the vehicle’s weight and the mission’s specifics. The simplest way to reduce ambiguity is to maintain a proactive licensing posture—verify weights, confirm intended routes, and confirm cargo categories before any dispatch. This approach aligns with broader safety standards and keeps operations aligned with the evolving regulatory landscape.

The conversation would be incomplete without acknowledging the role of official guidance. DMV offices and the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) provide the authoritative map for which licenses and endorsements apply to which loads. In practice, drivers and fleet managers turn to these sources to confirm the correct licensing class for a given operation. While the general rule about GVWR and CDL eligibility offers a reliable starting point, the letter of the law, especially for interstate work or hazardous materials, can alter a project’s licensing demands. The safest course is to verify, document, and re-check whenever a job presents a weight shift or a change in cargo type. For ongoing alignment with best practices, many operators also review broader industry standards that inform how weight, load placement, and vehicle combinations influence licensing decisions. Such standards echo the shared aim of keeping roads safe while enabling efficient and capable recovery and towing services. For readers seeking a concise consolidation of regulatory expectations, consider exploring the standardization in heavy-duty rescue operations guidance, which reflects how weight, equipment, and licensing interact in complex, high-stakes scenarios.

In the practical realm of fleet operation, this means more than a rule to memorize. It means building a culture of proactive compliance, where every flatbed task starts with a weight assessment and ends with a verified licensing plan. It means recognizing when a load profile requires a CDL, and when it does not, without letting assumptions drive the decision. It means training drivers to interpret GVWR and GCWR values correctly, to understand how towing a vehicle changes the weight picture, and to know when to seek endorsements or alternative routing. And it means staying curious about the evolving regulatory environment, knowing that interstate commerce, HazMat, and multi-trailer configurations can upend a straightforward weight-based calculation at any moment. In short, the weight equation is less about a single number and more about a disciplined approach to licensing that matches the realities of heavy towing on modern highways. For those who want to explore the regulatory backbone more deeply, the Federal FMCSA CDL Requirements page offers the formal, up-to-date guidance that every responsible operator should consult: https://www.fmcsa.dot.gov/leadership/education/cdl-requirements.

Internal link reference: For a broader perspective on how industry standards shape heavy-duty operations, see the discussion on Standardization in heavy-duty rescue operations. Standardization in heavy-duty rescue operations.

Weight, Warnings, and the CDL Crossroads: Do Flatbed Tow Truck Operators Need a CDL—and What About Hazmat Endorsements?

Do you need a CDL for a flatbed tow truck? The question sits at the intersection of weight, regulation, and responsibility. In practice, most flatbed tow trucks and the costs of operation push drivers into the CDL category, because the typical configuration quickly crosses the federal threshold. The key metric is not the truck alone but the combined weight of the vehicle and its payload. Federal law states that anyone operating a vehicle with a gross vehicle weight rating above 26,000 pounds must hold a valid CDL, and that a combination vehicle can change the calculation when the towed load is included. In the real world, a flatbed tow truck may weigh around 12,000 to 20,000 pounds empty, but when it hauls a typical vehicle, the total weight can easily exceed 26,001 pounds. Consequently, many tow operators require a CDL simply to perform routine roadside recoveries, especially when highway speed or interstate travel is involved. The practical implication is clear: the weight threshold is not a mere number; it is a living boundary that defines licensing responsibilities for a sector that relies on speed, safety, and access to the right lanes during emergencies. The moment you quantify the operation, the rules begin to unfold. A flatbed is built to carry vehicles; the GVWR on the truck itself is only part of the story. When a towed vehicle is added, the critical figure becomes the GCWR, the gross combination weight rating. If that number surpasses 26,001 pounds, a CDL becomes the standard requirement for the operator. Some states still require a CDL for any operator of a heavy tow truck regardless of the combination weight, while others apply the rule strictly to interstate commerce. The result is a patchwork of interpretations, which is why most operators who want to stay compliant schedule time to review the federal guidance and the state supplements before they decide which license class to pursue. It is also worth noting that there are exemptions and nuances: driving a vehicle in intrastate commerce with a lower weight might not require the same license as interstate operations, and certain specialized tasks draw additional endorsements beyond the base CDL. Hazards come in different forms. If your flatbed tow truck is tasked with moving hazmat, you must obtain a hazmat endorsement on your CDL. The endorsement is not handed to you with the standard license; it requires approval that hinges on background checks and a specialized written examination that covers the safe handling, packing, and transport of hazardous substances. The process is thorough for a reason: hazmat drivers must meet higher security checks and demonstrate a disciplined understanding of routes, placards, emergency response, and the potential consequences of a spill or exposure. Even if the gross weight would otherwise trigger a CDL requirement, the presence of hazmat moves the licensing needs into a stricter category. The endorsement is a credential that signals a driver has undergone additional training and is vetted for sensitive materials. For those considering a tow business that sometimes carries fuel, solvents, or other dangerous cargo, the hazmat endorsement is not optional; it is the gateway to compliant operation in those scenarios. What about operating across state lines? Interstate commerce imposes federal baseline requirements, but states retain the authority to add or adjust rules for intrastate journeys. In practice, many towing firms that perform roadside rescues, accident recovery, or fleet support find themselves traversing multiple jurisdictions. The safest approach is to align licensing with the broadest anticipated scope of travel while maintaining the flexibility to adapt to evolving regulatory expectations. The federal FMCSA guidance is the anchor, but the states’ DMVs supply the day-to-day criteria, exam procedures, and medical certification standards that define how you prove you are fit to drive a heavy tow truck on public roadways. The cadence of obtaining a CDL for a flatbed operator often begins with awareness, then assessment, then training. If the weight calculations suggest you will be operating over the threshold, you typically begin with a commercial learner’s permit, or its equivalent in your state, followed by required behind-the-wheel and classroom instruction. A medical examiner’s certificate is a recurrent obligation, ensuring you meet the federal standard for health and vision. It is not unusual for a towing business to fund training as part of a broader safety program, because the return on that investment is measured in fewer incidents, better fuel efficiency, and smoother on-road recoveries where response times matter. Another practical thread concerns documentation and ongoing compliance. You should maintain records of vehicle weight, the towed load, route plans for hazardous materials, and any endorsements attached to your license. If your fleet operates in emergency response or disaster scenarios, you may be called to demonstrate that your licensing and training align with the standards that govern such operations. This is not merely bureaucratic ritual; it translates into safer maneuvers, fewer permit delays, and clearer communication with dispatchers and law enforcement during high-stress situations. The modern tow operator is not simply a driver; they are a problem solver who must balance the physics of heavy machines with the ethics of safety, the discipline of regulation, and the unpredictability of the road. In the bigger picture, licensing choices influence not only individual careers but the reliability of emergency response across communities. A license class that matches the weight of what you haul, plus the appropriate endorsements when necessary, creates a predictable framework for scheduling, insurance, and fleet management. When a company invests in training and compliance, it also invests in public trust—the quiet confidence that a heavy tow unit is ready to operate in congested traffic, near damaged vehicles, or under winter conditions where friction and visibility are degraded. This is where the chapter of licensing connects with broader topics of fleet standardization and emergency readiness, which you can explore in resources dedicated to aligning policy and practice for heavy-duty rescue operations. For instance, a discussion of standardization and readiness offers a context in which licensing decisions sit alongside procedures, equipment checks, and driver performance metrics that complete a safe, effective response effort. fleet-standardization and emergency readiness. That connection helps readers see that licensing is not an isolated checkbox but a thread that runs through the entire operation, from the specifics of weight calculations to the strategic planning that supports quick, safe service to motorists in distress. To navigate this landscape with clarity, you should consult both your state DMV and the federal FMCSA guidelines. The FMCSA site provides the authoritative overview of CDL classes, the 26,000-pound threshold, and the process for obtaining endorsements, including hazmat. Your state DMV will translate those federal rules into the realities of testing, forms, fees, and the medical certification you must maintain while you operate. If you are building or refining a towing business, taking a current, thorough look at weight calculations is a good starting point. You should review whether your typical operations involve a towed load, the likelihood of crossing state lines, and whether you might encounter the transport of hazardous materials in your daily tasks. Even if your current workload seems modest, future contracts or on-call work can broaden the scope of what is required, so proactive planning pays off in smoother onboarding for new drivers and easier annual renewals. The decision to pursue a CDL, and which endorsements accompany it, is ultimately a blend of physics, law, and logistics. The physics is simple in principle: heavier rigs demand greater control, longer stopping distances, and more precise load securement. The legal framework is exacting and sometimes inflexible, designed to standardize safety across the tens of thousands of miles of road and the variety of loads that tow operators encounter. The logistics are practical: medical cards, written exams, background checks, vehicle inspections, and the administrative steps that keep a fleet compliant while still responsive to emergency needs. In this light, the CDL question is not a mere formality; it’s a decision that shapes the caliber of service you can offer. It determines which lanes you may travel, which jobs you can bid, and how you coordinate with dispatchers and law enforcement when time matters most. And while the threshold of 26,000 pounds is the touchstone, the hazmat endorsement adds a different dimension, one that signals a deeper commitment to safety and accountability. As the broader article will show, the answer to the opening question—do you need a CDL for a flatbed tow truck—depends on the specifics of weight, load, and jurisdiction, with hazmat adding a crucial layer of endorsement. The underlying theme is that licensing is a tool for safety, efficiency, and reliability in a service that touches people in stressful moments on crowded highways and slippery streets. For operators, the practical takeaway is straightforward: measure the combined weight where you operate, plan for the possibility of a CDL, and pursue the endorsements that align with your actual duties. And always verify with the FMCSA and your state DMV because rules can change, and the precise requirements can vary based on whether you move goods across state lines, transport hazardous materials, or maintain a fleet that routinely handles heavy, sensitive loads. The licensing decision, in other words, is a strategic part of building a responsible, capable towing operation that serves the public good, even in the most demanding conditions. For authoritative details on the CDL classes, weight thresholds, and endorsements, refer to the official regulatory resources. The FMCSA site is the central authority for CDL policy, with practical guidance on how to obtain credentials and manage endorsements. FMCSA CDL information.

null

null

Final thoughts

Navigating the requirements for operating a flatbed tow truck can be complex, particularly concerning the need for a CDL. Weight classifications, state regulations, combinations of vehicles, and the transportation of hazardous materials all play a crucial role in determining the necessary licenses. By understanding these critical factors and following best practices, you can ensure that your operations remain compliant and safe. Always make it a priority to consult your local DMV and stay updated on changing regulations to protect your interests and keep the roads safe.