For local drivers, auto repair shops, property managers, and HOA administrators, understanding the towing capacity of tow trucks is vital. Whether you are needing assistance for an emergency or managing parking issues, there’s a pivotal question: how many trucks can a tow truck tow? The following chapters will clarify how tow truck classifications, vehicle weight, legal regulations, special cases, and even road conditions influence the number of vehicles that can be safely towed. By the end of this guide, you will be equipped with the knowledge to make informed decisions concerning towing needs and services.

Tow Truck Capacity Unraveled: How Many Vehicles a Tow Truck Can Move at Once and Why It Is Not One-Size-Fits-All

Answering how many vehicles a tow truck can move at once requires nuance. Tow trucks differ in design, capacity and purpose, and the practical limit is shaped by weight balance and safety. In most everyday operations a single vehicle is moved at a time, but certain configurations and staged procedures can involve multiple steps rather than a single uninterrupted tow.

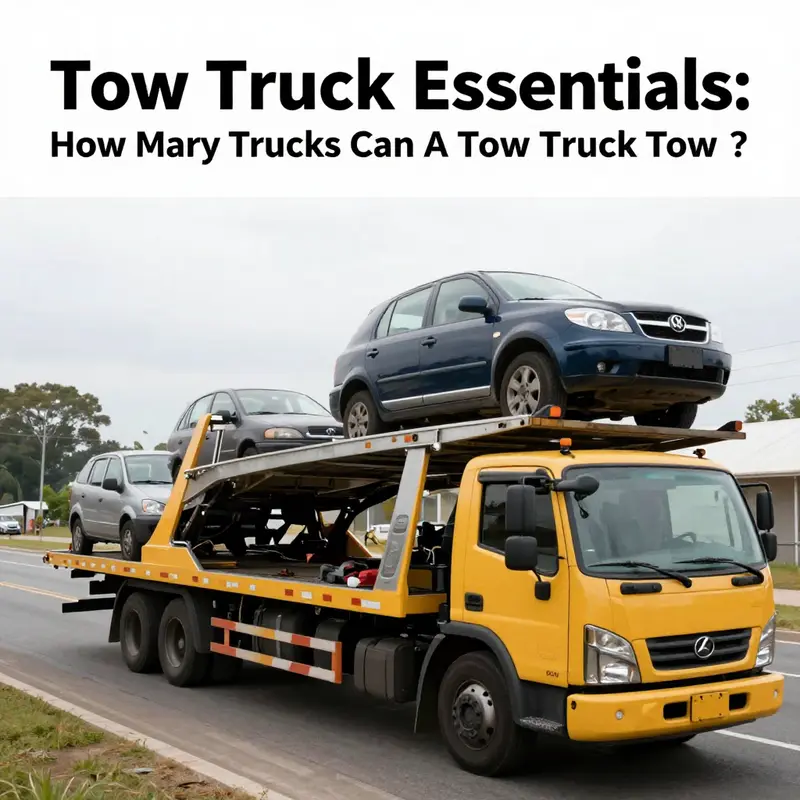

Industry classes help explain the landscape. Light duty tow trucks, often called Class A, are built for urban recoveries and commonly tow one car at a time. Heavier Class C wreckers are designed to handle large loads like trucks or buses, but they are not typically used to tow several vehicles simultaneously in one motion. In some long distance transports fleets may stage multiple vehicles on a specialized trailer, a controlled operation that is planned rather than a routine roadside tow.

The main constraint is safety. Weight distribution, braking capability, steering and suspension limits all govern how much load a tow truck can carry. Even when a larger unit could technically manage more weight, the risk of wheel lift, sway or trailer misalignment makes multi vehicle towing hazardous.

In practice, the standard scenario is one vehicle per tow. Multi vehicle moves occur only in exceptional circumstances, often involving separate recovery steps, multiple attachments, or specialized equipment and expert coordination.

Those who want more detail can consult operator manuals and standards documents that specify permitted load limits, attachment methods, and safety protocols for different vehicle classes.

Weight as the Verdict: How Tow Trucks Decide How Many Cars They Can Haul

Weight determines the practical capacity of a tow operation, shaping decisions about how many vehicles a tow truck can move in one maneuver. The calculation is not a simple headcount but a balance of the truck’s payload limit, axle load distribution, and regulatory constraints.

At the core are ratings like payload capacity, GVWR, and GCWR. The payload is what the truck can carry in addition to its own weight; the GVWR is the maximum weight of the vehicle when loaded; the GCWR accounts for the total weight of the tow vehicle plus the towed load. Operators must ensure neither the vehicle nor the combination exceed these limits, because exceeding them directly threatens braking, steering, tires, and overall control.

In everyday work, a light- or mid-weight tow truck typically handles a single passenger car. Larger, heavier rigs can tow two or three under proper conditions, with careful attention to weight distribution and rigging. For big operations, some configurations allow four to six smaller cars, but only if the total load remains within GCWR and the rigging preserves stability. Often, the faster approach is sequential towing: moving vehicles one at a time or in controlled sequences to maintain safety margins.

Equipment design matters: wheel-lift systems, booms, and stabilization features define which weight bands can be handled. Vehicle size and shape also influence capacity, because longer or wider cars demand more secure anchoring and balance.

Regulatory requirements weave through every decision. Local limits, clearances, and route-specific rules can cap the number of vehicles that can be moved at once. In practice, weight-first thinking and disciplined rigging deliver safer, more predictable outcomes than simply chasing a higher count. For readers seeking official guidance, manufacturers’ specifications and regulatory bodies provide the exact limits for each configuration. External reference: https://www.british-tow-truck.com/technical-overview-best-tow-trucks-specifications-applications

null

null

Weight, Wheels, and the Line That Holds: Demystifying How Many Trucks a Tow Truck Can Tow

When a tow truck arrives on a scene or at a yard, people often ask a deceptively simple question: how many trucks can you tow at once? The truth is that there isn’t a single, universal answer. The number depends on a mix of equipment, the size and weight of the vehicles involved, and the rules that govern safe transport on the road. In practice, the answer unfolds as a careful calculation rather than a magic number. A small, light-duty tow truck has a different ceiling from a heavy-duty wrecker, and even within those classes, the method of towing matters just as much as the mass of the cars being moved. This isn’t about bravado or efficiency alone; it’s about safeguarding people, property, and the vehicles themselves, all while staying within the boundaries of road regulations and engineering limits.

The most fundamental variable is the type of tow truck. Light-duty units—think compact, pickup-based models—are built for one vehicle at a time. Their winches and ramps are calibrated for steady, controlled recovery and transport of a single standard car. When a car is disabled or blocking a lane, the priority is to secure it safely, load it securely, and move it without creating new hazards. The single-vehicle norm reflects both the typical payload and the practicalities of maneuvering a loaded tow truck through traffic, around corners, and onto a ramp or carrier.

In the next tier, medium-duty tow trucks—models designed to handle more than one car under ordinary conditions—can usually tow two or three vehicles when space, weight, and road conditions permit. These units often employ more robust wheel-lift or dolly configurations, or a larger flatbed that can accommodate increased mass and longer wheelbases while preserving balance. Even with the added capacity, the dispatcher weighs the weight of each vehicle, its distribution, and the route’s grade. A rise in grade or a tight turn can shift the calculus from “two is doable” to “one is safer.”

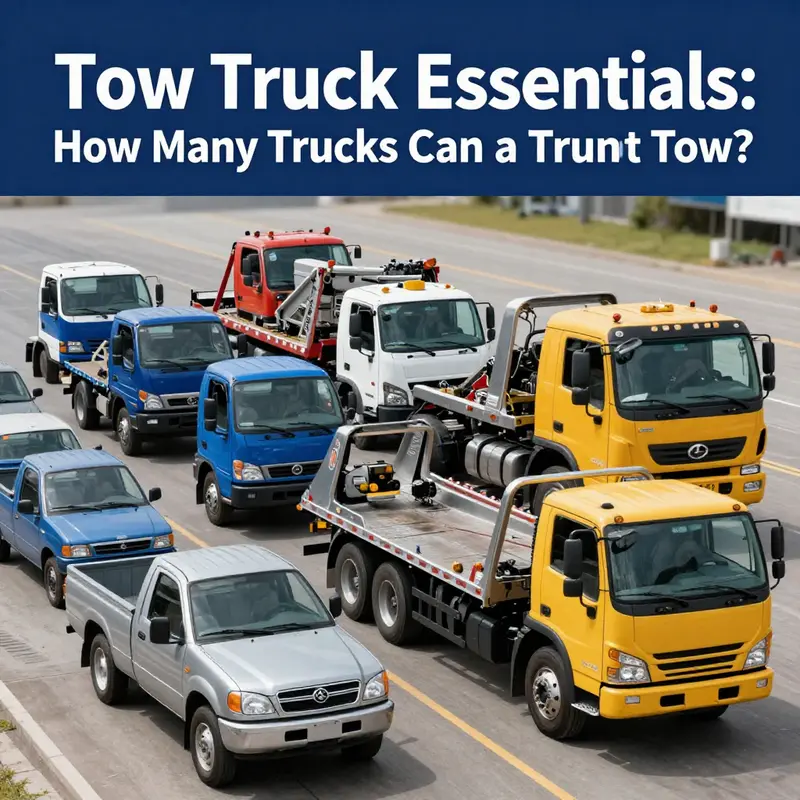

The upper end of the spectrum is occupied by large, heavy-duty tow trucks. These can carry more vehicles under certain circumstances, particularly when the towed cars are compact and light, such as small sedans or compact SUVs. In optimal conditions, a heavy-duty wrecker might move four to six smaller vehicles or equivalents. The practical limit, however, often shrinks to two or three when the vehicles are larger—think mid- to full-size SUVs and pickup trucks—because the combined weight plus the need to preserve proper weight distribution and braking becomes a critical safety factor. In some specialized long-haul operations, fleets have mounted trailers that enable moving several vehicles with one tractor-like tow truck, but those setups are rare, require meticulous planning, heavy-duty traction, and explicit regulatory clearance.

The chapter’s subtopic of special cases deserves more attention because it explains why the answer can swing dramatically. Flatbed tow trucks—often called rollback or slide-off models—bring the benefit of secure contact and minimal ground-off damage. A standard flatbed can typically carry one full vehicle on its hydraulically operated platform. In most situations, that means a single-vehicle transport, even though the bed’s length and stabilization mechanisms are designed to handle a variety of chassis and wheelbases. In some larger flatbeds, space can allow a second, smaller vehicle to sit side-by-side on the bed, but that configuration is not common and depends on precise alignment, weight balance, and the bed’s dimensions. The primary advantage of the flatbed remains safety and damage prevention, not the number of vehicles hauled at once.

Beyond flatbeds, a concept known among fleets as “tow trains” or multi-vehicle towing exists, though it is not a routine operation. In rare circumstances, a tow truck with specialized equipment—such as spreader bars, multiple chains, and trailers—can move two or three smaller vehicles in tandem with the main tow, effectively creating a line of four or five vehicles under one operator’s control. It is a complex maneuver that demands exacting coordination, strong power delivery, and careful route planning. The practice is typically reserved for non-emergency fleet moves over long distances or for controlled recoveries where the environment has already been rigged to support such a setup. The key takeaway is not that a tow truck can routinely haul a long train, but that the potential exists, contingent on equipment, training, and regulatory allowances.

In industrial and large-yard settings, the same principle applies with a twist. A lone tow truck may be part of a larger choreography, where one vehicle is pulled into position by one unit and then becomes a dedicated tow point for another. This isn’t the same as a single truck directly towing multiple vehicles, but it demonstrates how crews optimize throughput while distributing load and risk across a coordinated team. Safety remains paramount in these scenarios, with precise weight distribution, secure tie-downs, and verified clearance throughout the operation.

If we step back from the mechanics and consider the drivers’ perspective, the numbers are a map, not a mandate. A dispatcher assesses weight, length, and center of gravity for each car, the vehicle’s binding points, and the aging or damaged condition of the towed cars. Then, with the route in mind—corners, overpasses, and lane restrictions—the dispatcher selects a plan that minimizes risk while fulfilling the client’s needs. The planning layer is where experience matters most. It involves choosing the right equipment, calculating the combined weight, and imagining the worst-case scenario on each turn of the route. It also includes timing, as longer or more complex moves can require additional personnel or alternate paths to avoid restrictions and hazards. The process highlights how the question of “how many can be towed” quickly becomes a dialogue about safety, capability, and responsibility rather than a simple count.

For readers curious about the broader context of fleet operations and how standards shape these decisions, the topic is explored in community and industry discussions that often reference the practical realities faced by responders and recovery teams. To gain further insight into how fleets structure readiness and standardization in emergency and heavy-rescue operations, visit the Santa Maria Tow Truck Blog for perspectives grounded in day-to-day practice. Santa Maria Tow Truck Blog

In the end, the most honest, actionable answer is nuanced. In routine roadside service, the norm is one vehicle per tow. In specialized cases, with the right combination of flatbed capacity, power, and restraint systems, a heavy-duty operator can move more than one vehicle at a time. The possibility of a multi-vehicle conveyance exists, but it hinges on multiple conditions aligning: the weight of the cars, the geometry of the load, the strength of the securing hardware, and the legal envelope governing weight, length, and route safety. The industry’s collective experience emphasizes that safety and regulatory compliance trump any urge to maximize the number of towed vehicles in a single operation. This emphasis on safety is why the answer remains situational—no universal tally, only careful calculation and disciplined execution.

As you consider the technical details behind these operations, you may encounter literature that dives into the specifications of flatbeds, traction systems, and the evolving standards that govern heavy-duty recovery. A detailed exploration of contemporary flatbed specifications and industry performance offers a technical lens on how manufacturers design equipment to handle larger payloads and more complex loads. For a deeper dive into those standards and their practical implications, you can follow this external resource: https://www.towtrucknews.com/new-flatbed-tow-truck-sale-complete-analysis-of-standards-types-and-industry-performance/

Tow Capacity Under Pressure: How Road Conditions Reframe What a Tow Truck Can Haul at Once

Across the spectrum of roadside recovery, capacity is a moving target rather than a fixed quota. The ability of a tow truck to haul multiple vehicles depends on the vehicle weight and dimensions, the tow device rating, and the road conditions during the operation. In everyday practice, small light duty tow trucks seldom carry more than one car, while medium duty units commonly haul two or three in favorable conditions, and large heavy duty trucks can move four to six smaller cars under the right setup. Extreme configurations like multi vehicle transports are possible in specialized contexts, but require optimal conditions and careful planning. Importantly, these figures assume level ground, dry pavement, proper load balance, and adherence to weight ratings. When any condition shifts, the practical capacity diminishes.

Surface and weather are the first variables that alter the plan. Dry asphalt allows more margin, but rain, snow, or ice reduces friction and increases stopping distance. In wet or slick conditions, operators typically reduce the number of towed vehicles to maintain control and safe braking. Wet roads can also affect trailer sway and steering geometry, raising the risk of loss of control if the load is too ambitious.

Gradient and terrain add further anxiety: towing uphill increases engine load and reduces downward force on the towed units, while downhill segments stress braking systems. In either case, the safer choice is to reduce the load and keep a conservative setup.

Regulatory and safety considerations provide hard boundaries. Weight ratings, axle loading, and proper distribution are not negotiable, and when conditions degrade the operator should adjust downward rather than push the limit.

Ultimately, the theoretical capacity is a guide, not a guarantee. Real world towing emphasizes risk assessment, environmental awareness, and readiness to adapt. When conditions are favorable a large tow truck might carry several small vehicles, but under rain, grade, or traffic constraints, one or two units is a prudent cap. The aim is safe, predictable service that protects lives, property, and equipment.

Final thoughts

Understanding how many trucks a tow truck can tow involves several crucial aspects including classification of the machinery, vehicle weight, as well as regulatory and safety concerns. Each of these factors plays a vital role in determining towing capacity. As a local driver, auto repair shop owner, or property manager, having this information empowers you to make better decisions during roadside assistance situations. Seek towing services from providers who prioritize safety and adhere to legal guidelines; this will ensure an efficient and secure towing experience.