Imagine a scene where a tow truck, the very embodiment of vehicle recovery, finds itself in need of rescue. It’s a surprisingly common occurrence, rooted in various unpredictable situations. From mechanical failures to complex recovery operations at accident sites, tow trucks are not exempt from complications. Each chapter dives deep into understanding these scenarios—from breakage and recovery to the underlying mechanics and safety protocols involved in a tow truck towing another tow truck. We unravel the mystery of this unusual encounter while providing vital insights for local drivers, auto repair shops, property managers, and anyone operating in the automotive realm.

When Help Hires Help: The Delicate Art of a Tow Truck Towing a Tow Truck on the Road

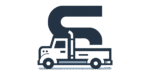

On the open stretch of highway, a scene that feels almost paradoxical unfolds: a tow truck, the very instrument of rescue, is itself tethered to another heavy recovery unit. The sight is jarring at first glance, yet it is a practical solution born from experience, planning, and a deep understanding of road safety. A tow truck towing another tow truck is not a common spectacle, but it is a recognized operation when the situation calls for it. It speaks to the resilience of a system built to keep traffic moving and to prevent minor breakdowns from becoming larger disruptions. What looks like a logistical oddity is, in practice, a carefully choreographed sequence orchestrated to minimize risk and maximize efficiency.

The moment a breakdown or a collision disables a tow truck, the human factors begin to matter as much as the mechanical ones. Operators arrive equipped with a clear plan. They assess the disabled vehicle, the traffic conditions, the weather, and the distance to a repair facility. The decision to bring in a second tow truck hinges on multiple variables: the severity of the damage, the weight distribution, the feasibility of on-site repairs, and the potential hazard posed by leaving the disabled unit in its current position. On a busy highway, even a small delay can cascade into additional incidents, so the clock and the safety margins are part of the equation from the very first contact.

Rigging a tow truck to haul another is a process that blends engineering rigour with practical know-how. The leading unit positions itself with precise alignment to the end that will be towed. The disabled truck is secured using heavy-duty chains and binders rated for the weight and dynamic forces involved. If the two vehicles share a similar wheelbase or weight category, the operator may opt for a wheel-lift approach, lifting a portion of the towed truck’s weight while keeping the majority on the road surface to preserve traction and control. In other scenarios, a dolly or a platform may be used to elevate critical wheels, reducing transfer of vibrations and reducing wear on sensitive components. Each choice has a rationale rooted in load distribution, braking dynamics, and the risk of uncontrolled movement.

Communication between operators is central to safety. A steady stream of radio calls, hand signals, and an agreed-upon set of cues keeps the movement predictable for other drivers. The trailing driver monitors the towed vehicle for any shift in weight or unusual sounds that could indicate a chain loosening or a binding that is not holding as intended. While the mechanical systems are robust, the human eye remains the most important sensor on the scene. The operators also continually re-evaluate the route, considering shoulder width, exit ramps, and the availability of a safe staging area for a potential reconfiguration of the rig. This adaptability is a core strength of professional towing, especially when the operation involves multiple large vehicles moving in close proximity.

Safety is not merely a checklist; it is a mindset that threads through every decision. The tow team uses conspicuous lighting to alert passing motorists, including amber beacons and reflective gear that guarantees visibility in changing light conditions. Traffic control may be necessary, sometimes requiring law enforcement or temporary lane closures to allow a slow, deliberate transfer of weight and steering responsibility. The edges of the road become a high-stakes workspace, and the operators treat every inch with deliberate care. The equipment itself—winches, chains, binders, and hydraulic systems—operates within tightly defined tolerances. Regular maintenance records and inspection routines underpin every move, ensuring that what looks like a routine recovery is, in reality, a carefully calibrated operation with a safety margin built in.

There is a broader logic at work too. Tow companies do not rely on a single vehicle to meet every contingency. Large fleets maintain a spectrum of capability, including heavy-duty models prepared to handle other tow trucks, heavy loads, or unusually difficult recoveries. In practice this means having backup equipment, trained personnel, and a well-practiced escalation protocol when a job exceeds the capacity of a single unit. In many operations, the moment a second tow truck is summoned signals the start of a joint protocol that has been tested in drills and refined through real-world experience. The outcome is not only the rescue of the disabled unit but also the preservation of safe traffic flow and public confidence in the roadside assistance system.

The scenario also sheds light on the transitional nature of towing as a profession. Tow trucks are designed to correct and remediate road hazards, but they are not immune to hazards themselves. A mechanical failure in a recovery vehicle can cascade into a dual-tow situation where one damaged unit must be stabilized and moved with another. In such moments, the operator’s understanding of traction, weight transfer, and steering geometry becomes as important as their ability to operate the winch. The job demands a calm focus, an awareness of the surrounding traffic, and the discipline to pause and reassess if conditions shift. Even when everything seems straightforward, the road remains a dynamic environment where surprises can alter the safest course of action in seconds.

The narrative of a tow truck towing another also intersects with the operational realities of fleet management. Some companies maintain dedicated emergency-response fleets, with explicit procedures for multi-vehicle recoveries. These procedures extend beyond the mechanics of hook-up and haul to the coordination of crews, the staging of additional equipment, and the preemptive planning that anticipates what to do if a tow truck becomes the one that needs rescuing. In this sense, the scene is a microcosm of how road safety and incident response depend on foresight, training, and disciplined teamwork. The industry’s emphasis on standardization and readiness surfaces in every practice, from how rigging points are selected to how drivers monitor tire pressures and fluid leaks during a tow.

Viewed in a broader frame, the act of a tow truck towing a tow truck highlights a quiet but essential truth about road safety: the system is designed to handle exceptions with competence and care. Even a seemingly paradoxical arrangement embodies a chain of safeguards that keeps traffic moving and minimizes the risk of secondary incidents. It is a practical reminder that every crisis on the highway is solvable when professionals approach it with method, foresight, and a shared commitment to safety. The operation becomes less about spectacle and more about the disciplined craft of recovery work, where every choice—how to attach a strap, when to engage a brake, and how to steer through a narrow stretch of shoulder—reflects a responsibility to the road and to the drivers who rely on it.

For those looking to understand the broader implications of such recoveries, the scene offers insight into how fleets prepare for the unforeseen. The same principles that guide a routine roadside assist—rapid assessment, secure rigging, clear communication, and a safety-first mindset—also inform the development of training programs and emergency-readiness initiatives. The aim is to reduce downtime, protect drivers, and keep lanes open whenever possible. In that sense, the moment when a tow truck tugs another into a controlled, safe move becomes a case study in the value of proactive planning and adaptive execution. It is not simply a recital of a rare event; it is a testament to the reliability and adaptability that underpins modern roadside assistance.

To connect these practical realities with a broader narrative of fleet resilience, consider the role of the operator as both technician and tactician. The operator must think several moves ahead, almost like a chess player, balancing the weight of the load, the angle of approach, and the evolving geometry of a moving convoy. The experience shows why ongoing training and access to well-maintained equipment are non-negotiable. It also demonstrates why some fleets invest in cross-training their crews so that a single incident can be met with a flexible, multi-skilled response rather than a rigid, single-solution approach. The road scene, then, becomes a living classroom where theory meets weather, traffic, and human judgment in a tense, ever-shifting environment.

From a reader’s perspective, this chapter may illuminate a little-known facet of road safety. The operation is not a detour from the mission of roadside assistance but an extension of it. It reveals the layered complexity behind a service many motorists take for granted. The next time a tow truck wheels into view behind a disabled vehicle, the scene may seem less simple and more strategic. It stands as a reminder that a tow truck that can be towed is part of a broader system designed to protect lives, reduce disruption, and uphold the public trust in the professionals who keep the roadways moving. The practical lesson is clear: when contingency becomes standard practice, safety turns from hope into habit, and the road travels forward with a little more certainty.

As a concrete reminder of the pathways that guide these operations, more formal guidelines exist and are continually refined through experience. For those who want to explore official procedures that frame recovery and towing across the industry, a widely cited resource can be consulted. It outlines the procedures, safety considerations, and best practices that underpin professional recoveries on a national scale, offering a detailed blueprint for how a tow truck towing a tow truck is executed with care and competence. External resources like these help translate the on-the-ground know-how described here into standardized, teachable content that supports every operator who faces the unusual, yet entirely resolvable, scenario of a tow truck towing another tow truck. See the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s vehicle recovery and towing procedures for authoritative guidance on these complex operations.

Internal linkage reference: for operator teams looking to align their practices with broader fleet readiness, many find useful guidance in their own fleet emergency response resources. These internal materials reinforce the idea that readiness multiplies safety and efficiency when the unexpected occurs on the highway. You can explore related resources that discuss standardization in heavy-duty rescue operations and other emergency-response considerations within a fleet context. The emphasis remains constant: preparedness transforms potential chaos into coordinated action, ensuring that a tow truck can become the safe hand that guides another toward a repair, a shop, or a safe stop rather than a hazard in motion.

External resource: https://www.nhtsa.gov/vehicle-recovery-and-towing-procedures

When Heavyweights Meet: The Silent Precision of a Tow Truck Towing a Tow Truck in Multi-Vehicle Recoveries

The open road does not always offer a simple sequence of events. In the quiet lull between red brake lights and the whine of a crane-like winch, a scenario unfolds that tests precision, patience, and teamwork: a tow truck, itself a heavy rescue instrument, being towed by another tow truck. This is not a spectacle of vanity or a curiosity for gearheads; it is a carefully choreographed response to disruption, designed to restore movement, protect responders, and prevent further harm. In the world of recovery operations, a tow truck towing a tow truck is not an anomaly but a disciplined extension of the same principle that governs every rescue: if a vehicle cannot move under its own power, a heavier, capable machine must shoulder the task. The rationale is simple, but the execution is anything but. Every decision made in the span of minutes can influence the flow of traffic, the stability of a damaged vehicle, and the safety of the crews standing in the roadway. The moment when a second heavy-duty unit steps into the scene is when the operation shifts from reactive to strategic, from response to controlled recovery. It is a moment that reveals the core of modern towing: adaptability anchored by training, standards, and a vocabulary shared by operators, dispatchers, and emergency services alike.

In a typical multi-vehicle incident on a highway, the first tow truck arrives to assess the scene and secure a path for clearance. When that initial vehicle has been compromised—perhaps a result of its own collision, damage from debris, or a mechanical fault—the next vehicle in the toolkit must assume a different role. Rather than simply pulling the disabled unit by a chain, the recovery team leverages a combination of specialized equipment and precise planning. The strategic choice often hinges on the weight and configuration of the disabled vehicle, the space available, and the location of hazards such as fuel spills or downed power lines. In such conditions, a second tow truck does not merely indulge an urge to help; it becomes a mobile remedy for a bottleneck that could cascade into secondary incidents if left unaddressed. The dynamic is a clear reminder that recovery is a system: one vehicle, one operator, and one plan must synchronize with the next to maintain momentum and safety on the road.

The hardware that makes this possible is diverse, each type offering different strengths that fit specific angles of the problem. Rotator trucks, for example, bring a rotating boom and an advanced winch system that can maneuver a damaged tow truck across a cluttered space with precision. This versatility becomes crucial when the disabled unit sits at odd angles or is partially blocked by another vehicle. The rotator’s ability to lift and reposition a compromised truck without additional damage is not just a technical feature; it is a safety assurance, reducing the risk of shifting loads that could unleash hazards downrange. In urban environments where lanes are narrow and the flow of traffic is dense, wheel-lift tow trucks offer rapid deployment and nimble handling. They can engage multiple contact points quickly, allowing responders to establish a secure bite on the towed vehicle without requiring extensive access around doors or undercarriages. When heavy lifting is unavoidable, 8-ton recovery tow trucks step into the breach. Their added capacity and stability provide a foundation for controlled lifts of heavier, more rigid chassis configurations. The choice among these tools is not arbitrary; it relies on trained assessment, careful scene reconnaissance, and a sober respect for the physics at play. A single miscalculation can convert a routine recovery into a dangerous lift, with consequences that stretch beyond the immediate roadway.

Behind the decisions on equipment is a team of operators who inhabit quite a different realm from the average driver. Their work begins long before the wheels kiss the asphalt at the crash site. It starts with a meticulous assessment of the scene: the position of vehicles, the slope of the roadway, the presence of spilled fluids, and the potential for hidden hazards such as mangled bars or fractured components. Operators must quickly translate those observations into a recovery plan that outlines the sequence of moves, the attachment points, the required towing gear, and the signaling plan for coordinating with other responders and with approaching traffic. The skill set here extends beyond mechanical know-how; it embraces communication, risk management, and an intimate literacy of safety protocols. Coordination with emergency services is not a courtesy but an operational necessity. Police, fire, and medical responders bring critical information about hazards and priorities, while the towing crew delivers a path to clear lanes and reduce exposure for everyone nearby. It is a collaboration built on trust, clarity, and the shared objective of moving people and vehicles to safer ground. The operator thus becomes a linchpin in the recovery chain, orchestrating the mechanical artistry of the lift with the strategic discipline of scene management.

The role of the operator at such a scene extends to a continuous evaluation of risk. The unstable dynamics of a partially immobilized vehicle can shift with the slightest disturbance from wind, traffic, or the movement of another heavy unit. That is why the equipment choice is always matched to a risk calculation: will a rotator’s multi-angle capability offer a safer approach, or is a wheel-lift sufficient for speed and maneuverability in tight spaces? Will an 8-ton unit deliver the stability needed to support a heavy configuration, or would it introduce more force into an already fragile situation? The operator must also plan for contingencies, such as the possibility of secondary crashes or the discovery of spilled fuel requiring rapid containment. And all of this takes place with an awareness of the broader context—how the incident fits into the day’s traffic patterns and how the recovery will satisfy the demands of downstream responders and motorists alike. This is not a solo performance; it is a chorus of expertise that must harmonize under pressure.

The efficiency and safety of these operations matter not only for those directly involved but for the traveling public who rely on roads to be cleared promptly and predictably. A well-executed recovery that successfully tugs a tow truck onto a stable lift often becomes the quiet pivot that minimizes the risk of secondary collisions and creates a safer corridor for rescue teams and tow crews to work. Timeliness matters, yet it is the balance of speed and control that preserves safety. A misstep—over-torque, an abrupt shift, or an unsecured load—can set off a chain of events that make the situation worse before it improves. Therefore, the procedural discipline—prioritizing scene safety, securing traffic, and establishing clear communication channels—remains the backbone of every successful operation. The goal is not to display horsepower but to demonstrate an efficient, measured, and adaptable approach to recovery that respects the integrity of every vehicle on scene and the lives of people nearby.

As a practical resource for professionals and planners alike, the body of knowledge surrounding these operations emphasizes standardized approaches and shared best practices. For those interested in a deeper dive into how standardization shapes heavy-duty rescue operations, Standardization in Heavy-Duty Rescue Operations offers a comprehensive overview of the approaches that keep complex recoveries predictable and safe. The chapter on equipment roles, the emphasis on operator training, and the emphasis on cross-agency coordination all reflect a field that is continually refined through experience and formal guidance. While every scene is unique, the underlying framework remains consistent: assess, plan, execute, and reassess, all while maintaining safety margins and clear lines of communication.

The broader lesson emerges when we consider how such recoveries fit into the everyday fabric of road safety and emergency readiness. They illustrate how fleets rely on standardized protocols, sparing crews from improvisation under pressure. They also highlight the importance of time-tested skills: the ability to read a scene, anticipate the forces at play, and guide a weighty piece of equipment toward a precise outcome without creating new hazards. In practice, this means training that emphasizes not just the mechanics of lifting but the choreography of moving a structure that weighs tons in a dynamic, high-stakes environment. It means investment in tools that broaden the operator’s repertoire—from rotators that can reach awkward angles to wheel-lifts that maximize speed without sacrificing control. It means a culture where every shift starts with a safety briefing, every attachment point is treated with respect, and every movement is communicated clearly to the team and to nearby drivers. In that sense, the sight of a tow truck towing a tow truck is less a spectacle than a testament to the disciplined complexity of modern road rescues: two heavyweights, one goal, and a network of professionals who keep the lanes open even when the road looks most uncertain.

For readers seeking further perspectives on related operational readiness and the practicalities of recovery logistics, consider exploring resources that address broader fleet emergency readiness and standardization in heavy-duty rescue contexts. These dimensions reinforce the idea that a single, high-stakes maneuver—such as towing one tow truck with another—can reveal the fabric of a recovery program: the training behind the wheel, the equipment that makes the lift possible, and the coordination that keeps the highway moving while a scene is resolved. In the end, the legitimacy of this practice rests on a simple premise: recovery is a system that works best when every link in the chain is clear, capable, and prepared to act.

External link for deeper technical context: Tow road recovery guide.

Carrying the Carrier: The Real-World Logistics and Limitations of Towing a Tow Truck for Equipment Transport

A tow truck towing a tow truck is a scenario that rarely makes the daily schedule of a towing fleet, yet it represents a crucial capability in the infrastructure of recovery and logistics. It is not merely a curious image but a practical solution born of the same engineering principles that power every heavy-duty operation: if a vehicle cannot move under its own power, a capable partner must move it. In many contexts this becomes most visible when a disabled recovery unit must be relocated, when a damaged responder is stripped of mobility after a multi-vehicle incident, or when a fleet needs to reposition a heavy asset without risking further on-site damage. The operation sits at the intersection of planning, physics, and policy, demanding precision in every link of the chain from load planning to securement, from route selection to compliance with weight and road-use rules. It is not an activity that can be improvised without consequence, yet when done correctly it underscores the resilience and adaptability of heavy-duty road services. To understand the logistics, one must start with the vehicle configurations commonly employed for this task. The carrier chosen to move another tow truck is typically a flatbed, sometimes referred to as a rollback, or a specialized transport trailer designed to handle extreme weights. The appeal of a flatbed lies in its ability to lift the towed vehicle so that its wheels do not contact the roadway during transit. This arrangement protects tires, suspensions, and axles from road wear and tear while keeping the entire mass securely supported by the platform. Yet flatbeds are not a universal solution. In some regions and in certain insurance circles, there is increased scrutiny of loading procedures for oversized, heavy-to-towed gear. Critics point to the risk of shifting loads during loading and unloading, unstable fastening surfaces, and the complexity of securing two heavy machines in close proximity. Even so, the flatbed remains a staple for industrial applications—where load integrity and off-road or remote-site mobility are paramount—because it minimizes surface contact and concentrates restraint on fixed points designed for high-torque, high-load applications. Weight and balance dominate the calculus of feasibility in any tow involving a towed tow truck. The combined mass of the carrier and the towed vehicle must satisfy legal and structural limits, including axle load ratings and the vehicle’s gross vehicle weight. The moment you exceed these limits, braking efficiency falters, steering becomes imprecise, and the suspension bears a burden it was not engineered to carry. In practical terms, the operator must map the center of gravity relative to the axles, confirm tire load distribution, and ensure that the attachment points and restraint systems can withstand the expected forces, including wind gusts, road irregularities, and sudden maneuvers. The load distribution also shapes the route and the driving strategy. A path that is smooth and predictable minimizes the likelihood of a dynamic shift that could compromise control. The driver must anticipate long descents, sudden stops, and the need for longer braking distances, all of which are intensified when the vehicle ahead is a heavy, non-driving asset tethered to a carrier. The actual loading method into the carrier is a delicate sequence of steps that demands precision. Flatbeds excel because they can accommodate the full height and width of the towed unit while allowing the operator to secure the vehicle with multiple, redundant restraints. Heavy-duty straps are anchored to chassis points designed to absorb the recoil of the combined mass; wheel chocks, when used, stabilize the towed vehicle and prevent any forward or backward movement during loading and securing. A well-executed setup includes a comprehensive plan: verify the towed truck’s braking and steering systems prior to lifting, inspect the attachment points for wear, and implement a double layer of protection against strap slippage or anchor failure. Securing the tow truck demands a methodical approach to avoid any shift that could cause the carrier to tilt, rack, or even roll. In this high-stakes context, you cannot rely on a single strap or a single point of restraint; redundancy is a safety imperative. The decision between a flatbed, a dolly system, or a dedicated transport trailer is never purely technical. It is a function of weight limits, road conditions, and the realities of the operation’s geography. A dolly system can be advantageous when there is a need to minimize the height of the towed vehicle on a standard carrier, or when the distance between the vehicles’ axles must be bridged without sacrificing maneuverability. However, dolly configurations introduce their own complexity in terms of steering coupling and the potential for tire and wheel alignment issues on the towed unit. A purpose-built transport trailer, while offering maximal stability for extreme weights, imposes cost and regulatory overhead that may not be practical for shorter relocations or operations where rapid deployment is essential. The core challenge remains: balancing protection of the equipment, safety of the operation, and the total cost of moving a machine that itself moves other machines. The financial and logistical calculus grows heavier when one factors in the operational footprint of a heavy tow operation. The vehicles involved are not merely larger than typical tow trucks; they require specialized maintenance, fuel strategies, and driver training. Heavy-duty recovery vehicles—those designed to handle six-wheel or eight-wheel configurations—are engineered for rugged conditions and the demands of remote environments. Their dispatch may be driven by the necessity to move between distant job sites or to position a fleet for a large-scale response to a disturbance. The cost is not solely the vehicle’s purchase price; it extends to maintenance cycles, tire life, hydraulic systems, and the wear-and-tear on the mounting and securing hardware that keeps the load intact. In city environments, maneuverability becomes a constraint as well. A vehicle designed for open highways and rough terrain performs differently in traffic, on narrow streets, or at intersections with limited turning radii. Fleet planners must weigh the fiscal benefits of having a capability against the operational friction it introduces in dense urban contexts. The procedural discipline surrounding this operation is as important as the hardware. Pre-load inspections, a well-drawn securement plan, and a permit-compliant routing strategy are not mere formalities. They are safeguards against a cascade of failures that could escalate into road hazards or costly downtime. The securement plan should account for potential strap elongation, anchor point fatigue, and dynamic loads introduced by road irregularities. Additionally, the operator must monitor for environmental and situational factors—weather, road surface, traffic density, and sight distance—to decide whether the move should proceed or be rescheduled. Training is not a one-off event but a continuous commitment. Operators must be conversant with the nuances of heavy-load dynamics, know how to respond to a strap failure, and remain proficient in the emergency procedures necessary to stabilize a compromised load on the shoulder of a highway if a problem arises. These considerations sit within a broader ecosystem of standards and practices that govern heavy-duty logistics and recovery. In this field, there is a track record of formalization and standardization that helps fleets operate more predictably under pressure. For those who want to explore how such standardization informs heavy-duty rescue and transport, see the discussion on standardization in heavy-duty rescue operations. This thread links to a broader body of work that examines how fleets calibrate equipment, procedures, and training to ensure reliability across varying scales of operation. Such standards are not abstract; they translate into the everyday decisions that keep a heavy tow moving when the margin for error is measured in inches and seconds. Ultimately, the viability of towing a tow truck hinges on rigorous assessment and disciplined execution. It requires choosing the right tool for the job, aligning it with weight and balance constraints, and applying a secure, redundancy-driven approach to attachment and transport. It requires a recognition that every component—from anchor points to wheel chocks, from hydraulic lift to communications with dispatch—contributes to a successful move. And it requires acknowledgment of the limits that govern these machines: the legal limits on road weight, the technical limits of the equipment, and the financial limits of what a fleet can afford to deploy in service of a remote or urgent mobilization. When those factors coalesce—sound equipment, a robust risk assessment, trained personnel, and precise execution—the operation becomes less a spectacle of necessity and more a quiet testament to the engineering discipline that makes a tow truck capable of towing another tow truck, moving not just one vehicle but a chain of assets that keeps critical services in motion. External reading on regulatory context can be found here: https://www.transport.gov.sg/road-safety/vehicle-transportation-and-loading-rules/vehicle-load-limits-and-securement-requirements.

Tow Within the Line: The Subtle Mechanics of a Tow Truck Towing Another Tow Truck

A tow truck towing another tow truck is a scene that can feel almost clinical in its restraint. It is not about spectacle or brute force, but about a precise orchestration of weight, leverage, and motion. The rarity of the sight only heightens its focus, because every inch of roadway becomes a potential point of failure if the operation is not treated with the care it demands. At its core, this is a disciplined exercise in applying force safely to a load that has similar mass, and sometimes more, than the vehicle performing the towing. The context matters as much as the mechanics: a disabled tow unit may need rescue after an accident, or a fleet might require a deliberate relocation of a heavy asset from one site to another. In such moments, the physics do not vanish; they become the measured steps a skilled operator follows to keep a complex chain of motion under control.

The most immediate factor in any tow is weight and inertia. A typical full-size tow truck can weigh roughly between 15,000 and 30,000 pounds, depending on configuration. This is not mere heft; it is a reservoir of kinetic energy that must be managed at every transition—from idle to pull, from straight line to a negotiated turn, from slow creep to steady acceleration. The towing system must be prepared to grip and guide that energy without surprise. It starts with the winch, the primary device that converts electrical or hydraulic power into controlled pulling force. A winch rated well above the expected load—often 30,000 pounds or more—is essential, and the cable itself must be designed for heavy-duty use. A failure in the cable under load is more than a breakdown; it is a dangerous moment that can cascade into loss of control of both vehicles. The operator’s hands are not just steering; they are modulating tension so that no sudden yank transmits through the towed unit. This careful modulation is what keeps the tow quiet and predictable, even when gravity or slick pavement tries to stage a different outcome.

The chassis of the towing vehicle must also be prepared for a dynamic, heavy-duty operation beyond ordinary towing. Reinforced frame rails and suspension systems become the quiet backbone of the mission. The extra mass of the towed truck doubles the expected dynamic load on the frame and on the suspension, especially during deceleration, uphill segments, or uneven surfaces. A robust chassis is not a luxury here; it is a prerequisite. It lends the towing platform the stiffness to resist sagging, the stability to resist sway, and the durability to survive the vibrations of long transfer under load. The towed vehicle, too, must be treated with respect. Wheels must be immobilized to prevent any roll, and wheel chocks become a small but essential line of defense against creeping movement as the trucks settle into their arrangement.

Traction is another critical axis in this operation. The towing and the towed units rely on their tires to deliver grip across the contact patch while the load is being managed. On loose or slick surfaces, chains or specialized tread patterns may be used to supplement traction. The operator must anticipate how weight shifts as the sequence of movement unfolds: the moment the winch begins to pull, inertia shifts, and the front of the towed vehicle may lift or buckle slightly if the load is not evenly distributed. This is why proper securing arrangements matter as much as power—both wheels of the towed truck must be restrained, and the towed chassis must maintain alignment with the towing point to avoid binding forces that would feed back through the hitch, the bar, or the bed.

Connection methods matter as well, and this is where the difference between a high-risk, tension-driven approach and a more stable, platform-based method becomes clear. The two broad options are direct tie methods, often associated with hook-and-chain systems, and more modern flatbed arrangements. In the scenario of towing one tow truck, a flatbed approach frequently offers the most advantages: it provides a stable platform that minimizes the chance of undercarriage damage to the towed vehicle and reduces the risk of mechanical failure during transit. When space and weight allow, a flatbed can cradle the second tow unit in a way that spreads the load evenly along the chassis while presenting a controlled surface for ramping and loading. It is not merely a matter of aesthetics or convenience; it is a design choice grounded in engineering resources that consistently report reduced risk with flatbed transport compared to traditional methods. The principle holds in practice: when a vehicle cannot move under its own power, the system should aim to move it with controlled support, not with abrupt or awkward force application.

A towing operation of this type also foregrounds the human element. Operator skill and situational awareness are central to success. The control of acceleration, braking, and turning must be coordinated with the securing and lifting processes. Smooth, anticipatory actions prevent jolts that could bend frames, shear fittings, or unsettle the alignment between tow and towed units. Because the load is substantial, the operator often relies on methodical pre-trip checks, route planning to avoid sudden grade changes or tight corners, and continuous monitoring of the weight transfer that occurs as momentum shifts. Realistic training, including simulations and exercises that reuse the same fundamental principles, becomes an important part of keeping the crew ready. Even in a field operation, the aim is to reproduce a disciplined sequence that reduces risk and fosters confidence when real vehicles are involved.

The practical logic of this kind of tow also sits within a broader context of safety standards and operational readiness. In large-scale recovery scenarios, a single tow truck may already be compromised; the second unit is then tasked with not only moving the other heavy asset but also coordinating the upstream and downstream steps of the response. This kind of coordination echoes the ongoing conversation about standardization in heavy-duty rescue operations. The goal is to translate the specifics of one emergency into repeatable, safe practices that can be taught, audited, and refined. It is this alignment between theory and practice that turns a rare contingency into a defensible procedure rather than a dangerous improvisation. For readers who want to see how these general principles map to real-world policy and practice, the linked discussion on standardization in heavy-duty rescue operations offers a useful frame of reference.

In reflecting on why a tow truck might end up towing another tow truck, the answer lies in the same logic that governs any recovery or transport operation. If the vehicle cannot move of its own accord, a second, capable machine must provide the necessary mobility. But the success of that action depends on more than raw horsepower. It depends on foresight, on a secure mechanical interface, and on a disciplined approach to speed, load distribution, and route safety. It requires choosing the right connection method for the given weight and conditions, selecting a secure means of immobilization for the towed unit, and maintaining vigilant control so that the entire system behaves as a single, well-behaved entity on the road. In this sense, the operation reveals a quiet truth about heavy-duty towing: the strongest force is not the winch alone but the fusion of robust equipment, careful plan, and skilled hands guiding everything with calm precision.

For practitioners seeking deeper engineering insight, a detailed technical reference on the design and performance of flatbed tow trucks provides a rigorous companion to this discussion. External resources that examine the structural implications of a 6×4 flatbed design and its ability to handle dynamic loads offer a practical extension of the concepts discussed here. External resource: 6×4 Small Flatbed Tow Truck Guide: Composition, Structure, and Performance for Engineers.

Internal link note: this discussion ties into broader conversations about the standardization and training frameworks that govern heavy-duty rescue operations. See the overview on standardization in heavy-duty rescue operations for how these principles translate into shared procedures, checklists, and competency benchmarks across fleets.

In summary, a tow truck towing a tow truck is a convergence of heavy physics, deliberate engineering choices, and disciplined human practice. It is not merely a mechanical possibility but a carefully managed sequence that seeks to minimize risk while delivering reliable movement. When executed with the right equipment, the right securing method, and the right operator mindset, the improbable becomes routine, and the road receives yet another instance of careful coordination over chaos.

When Giants Align: Safety, Strategy, and Protocols for Tow-Truck to Tow-Truck Recovery

Two heavy, purpose-built machines share the road in a scene that is rare and technically exacting: a tow truck towing another tow truck. The situation sounds almost paradoxical, but in the world of heavy-duty recovery it is a calculated necessity. A disabled or damaged tow unit on a highway or at a worksite can no longer perform its own rescue, and the only practical way to move it to safety or to a repair bay is to bring in a second, equally capable vehicle. The different roles in this choreography—the helper, the lifter, the stabilizer—must be understood not as separate tasks but as a single, integrated sequence. Safety sits at the center of that sequence, not as an afterthought but as the guiding principle that shapes every动作, every decision, every hold secured against unpredictable conditions. The scene demands more than brute force; it requires precision, planning, and disciplined communication to keep both trucks and any nearby people out of harm’s way while the equipment remains intact and functional for the next phase of repair or transport. In this context, the principle that underpins the entire operation is simple and universal: if a vehicle cannot move under its own power, it must be moved with care, and that care begins with a clear understanding of the weight and structure at play and evolves into a methodical set of procedures that keep leverage and momentum in balance rather than allowing one miscalculation to cascade into an uncontrolled event.

Weight and structural complexity define the core challenge of a tow-to-tow recovery. Both vehicles are heavy-duty machines with specialized components designed to endure severe service conditions. When a second tow truck is called into action, the combined mass becomes the limiting factor that defines the choice of equipment and the rigging approach. The flatbed, also known as a rollback or slide-bed tow truck, is the instrument of choice because its hydraulically operated platform can tilt, slide, and lower to ground level, allowing the entire towed unit to rest on the bed with all four wheels off the ground. This not only eliminates wheel-ground contact that can worsen frame or suspension damage but also stabilizes the two vehicles as a single load rather than a moving cluster of parts with uneven contact points. The flatbed’s design supports a secure loading process where the towed vehicle’s weight is distributed across the bed, and its center of gravity remains within the controlled envelope of the towing vehicle. In contrast, wheel-lift systems, while useful in many scenarios, introduce slower setup times and a higher risk of frame or suspension damage when attempting to cradle a disabled tow truck. The decision to use a flatbed is a practical choice born from an understanding of how the forces generated during loading, transport, and braking translate into real-world safety outcomes.

Capacity is the next boundary that must be respected. The towing vehicle must possess sufficient lifting capacity and overall gross vehicle weight rating to lift and secure the disabled unit without reaching the limits of the equipment. This is not a matter of preference but a matter of physics and risk management. If the combined weight of the two trucks approaches or exceeds the towing unit’s GVWR, the operation becomes unstable. The operator must verify the rated hoist capacity, bed weight limits, and the available arrestment points to ensure a safe, controlled lift. Every lifting point, every attachment point, and every anchor must be chosen with a deliberate eye on the potential for dynamic loads as the vehicle is rolled onto the flatbed. A single miscalculation here does not simply strain a component; it could permit a shift that propagates through the rig, compromising the restraint system and the integrity of the bed itself. Once the decision to proceed on the flatbed is made, the crew shifts from planning to execution, but the planning never ends. It simply becomes more granular, detailing how each strap, chain, and binder is positioned to minimize movement and maximize stability throughout the transfer.

Securing the disabled unit is the second half of the securing equation. High-strength straps and chains are the primary tools for preventing any shifting or sliding once the vehicle is on the bed. The technique matters as much as the equipment. The operator must inspect all tie-down points and verify that the lashings engage strong, stable locations on both vehicles, not onto vulnerable components such as fragile trim or non-load-bearing members. Redundancy matters here; the use of multiple tie-downs spread across strategic points reduces the risk that one failed strap will unleash a dangerous sequence of movement. The pre-load state matters too: straps must be tensioned sufficiently to hold the unit without allowing slack that could turn into a dangerous whip under acceleration or braking. A pre-operation inspection extends beyond the mechanical to cover the hydraulic systems, winch integrity, and the overall health of the bed’s tilt and slide mechanism. Leaks, worn lines, or corroded fittings can become sources of hydraulic loss precisely when you need the system to stay predictable. Every gauge and control should respond as expected to test actions before the operation begins, because a moment of uncertainty in the heart of a lift can multiply as you move.

Communication binds the technical elements into a coherent operation. Clear orders, unambiguous signals, and precise timing convert a potentially hazardous sequence into a controlled procedure. In the field, radios serve as the backbone of coordination, but hand signals remain essential when radio clarity is compromised by weather, distance, or noise. The crew may designate specific roles—one person focused on rigging, another on bed positioning, a third on traffic management, and a fourth on monitoring the towed unit’s alignment and restraint. The ability to anticipate problems before they become real emergencies is born from this disciplined communication and the shared mental model that everyone operates with. It is not enough to know what to do; everyone must know when to do it and how their action interacts with others’ actions. In tight spaces, on uneven terrain, or near moving traffic, even small delays or misreads can magnify risk. The measured rhythm of loading, securing, testing, and moving must be practiced until it becomes second nature, a silent choreography that keeps a high-stakes operation from becoming a statistic.

The operational protocols that govern these maneuvers tie the individual skills to a broader framework of safety and efficiency. Any heavy-duty towing operation involving more than one vehicle belongs to a specialized discipline that demands training. The personnel present should hold credentials and experience in heavy vehicle recovery, with hands-on familiarity with flatbed loading, winching, and restraint systems. The protocols emphasize caution about distance and duration; towing a disabled tow truck over long distances is discouraged unless it is absolutely necessary, because the longer a trailer is on the road, the greater the chance that equipment may fail or a new hazard may arise. When a wheel-lift model is considered, the guidelines generally favor flatbeds for this specific task due to the stability and reduced risk of frame or suspension damage, as noted in industry guidance. These preferences are not arbitrary; they reflect an accumulated body of knowledge about how the structure of heavy vehicles responds to the combined loads of recovery and transport, and how different rigging approaches influence the likelihood of a safe outcome.

Recovery operations of this magnitude rarely happen in isolation. In larger incidents on congested roadways, the first tow truck might be immobilized or compromised, and a second, more capable vehicle is called to complete the job. The stakes rise quickly as the scene becomes a complex system of moving parts, traffic considerations, and evolving conditions. In such contexts, the decision to use a flatbed is driven by the need to reduce movement and protect both vehicles from further damage while preserving the rest of the fleet for ongoing responses. It also highlights the importance of standardization—how consistently trained teams approach similar situations, how they communicate, and how they apply the same safety logic to a range of scenarios. The value of standardization in heavy-duty rescue operations is underscored by the need to translate this exacting knowledge into predictable, repeatable performance across many crews and locations. For those seeking deeper, field-ready guidance on this topic, see the resources on standardization in heavy-duty rescue operations and the broader emergency readiness framework.

The practical takeaway from all this is not merely that two large tow trucks can work together, but that they must do so with a disciplined, safety-first mindset that treats every rigging point as a potential failure point and every movement as a risk to people and machines. The sequence—from choosing a flatbed to securing with appropriate lashings, from performing a thorough pre-operation check to enforcing clear lines of communication, from adhering to a vetted protocol that discourages long-distance tows unless necessary—forms a comprehensive safety net. It is a reminder that even the most confident operator must respect the complexity of what is being moved and the fact that the vehicle receiving the lift often contains the same critical systems the rest of the fleet depends on for hauling, maintenance, and rapid response. In this carefully managed balance of force and restraint, the tow operator transforms a seemingly paradoxical act into a precise, controlled procedure that keeps everyone on the road safer and the operation productive. To learn more about the standards behind these practices and how they inform everyday field decisions, the related professional guidance can be explored through the linked resource that centers on standardization in heavy-duty rescue operations.

External resource: For further guidance on best practices and industry standards related to heavy-duty towing operations, refer to the National Association of Fleet Administrators Towing Safety Guidelines: https://www.nafa.org/resources/towing-safety-guidelines

Internal link: For a deeper discussion on how standardized approaches shape field operations, consider the concept of standardized procedures in heavy-duty rescue operations: standardization in heavy-duty rescue operations

Final thoughts

The image of a tow truck rescuing another may be rare, but it sheds light on the inherent complexities of our transportation ecosystem. It underlines the value of robust logistics, effective protocols, and safety considerations that protect every road user. Whether facing a breakdown or engaging in large-scale recoveries, understanding the nuances of these scenarios equips us all—drivers, operators, and repair professionals—with the wisdom needed to react aptly. Embracing the idea of mutual aid promotes a safer community for everyone who occupies our roads.